Where The Wheel of Time fits

I'm a little ashamed to admit this, but I'm about a fourth of the way through Book Nine of Robert Jordan's marathon of a fantasy series, The Wheel of Time.

I'm ashamed to admit it because I don't want to admit to myself (or to you) that I'm a nerd.

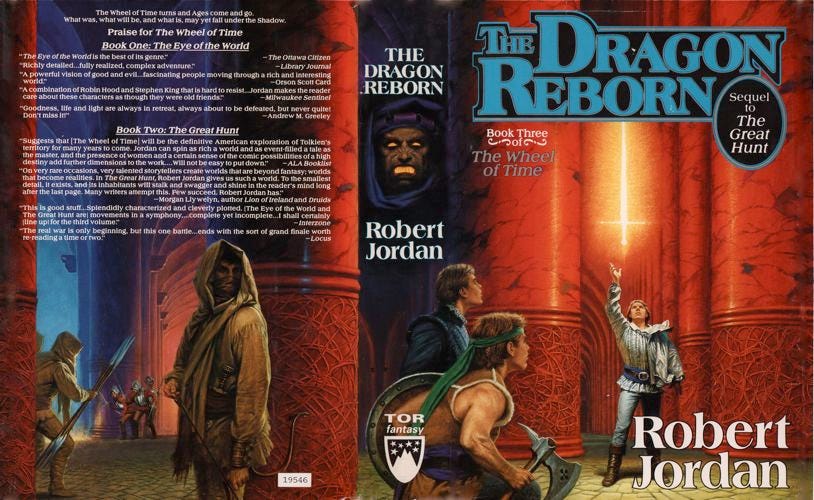

But, let's be real: I've read eight books that have titles like A Crown of Swords and The Dragon Reborn and The Path of Daggers and feature covers like this:

And, to make matters even worse, I'm planning on reading five more of these guys to finish out the 14-book saga.

The data is pretty clear: If I'm not a nerd, I'm doing a very good impression of one.

Which is totally fine, I guess, except that it doesn't quite fit with my self-image of "moderately athletic and mostly cool." That disconnect leads to cognitive dissonance, which leads to my mild shame.

But enough about my issues; I gave enough space to those last week. Treat all that's above as an aside, and bear with me as I get to my main point today:

The Wheel of Time is fascinating.

I'm not necessarily talking about the story itself; I'd rate the story as "decent," which I guess is kind of sad considering the amount of time I've put into reading it.

No, what I think is more fascinating is how The Wheel of Time fits into this very narrow cultural space after Tolkien and before almost everyone else.

Tolkien, for those of you who have avoided Jeff Bezos' omnipresent ads and every work of fiction since 1950, is the guy who wrote The Lord of the Rings. Pretty much everyone loves The Lord of the Rings. There are many, many reasons for that, but I think one of them is the series' powerful portrayal of good and evil.

There's no ambiguity to the morality of Middle Earth. Good is really good. The books' friendships (especially the bond between Frodo and Sam) are heartwarming. The hobbits' Shire is idyllic. The story's heroes are noble.

And evil is really evil. Mordor, the home of the villain, is a smoking, ash-shrouded wasteland. The Ring literally turns Gollum into a monster.

Our world isn't so black and white, of course. Most of our moral choices are muddied to a dull, blended gray. But in Tolkien's world, the muddy glass of water has settled and the dirt is distinct. Reality has been distilled so that goodness literally glows and evil is visibly monstrous. It's compelling. It's beautiful.

It's also a wonderful setup for subversion.

George R.R. Martin's incredible Game of Thrones series is the most popular example of this; Martin takes the idea of Middle Earth and flips it on its head. There aren't good guys and bad guys in his world, at least in any meaningful sense. The only character who might purely be a hero (Ned Stark) is killed off before the first book gets close to its climax, and in what became the most famous television scene of the past 20 years, the character closest in line to that claim (Robb Stark) dies in horrific fashion not long after.

Martin's world of Westeros is great.

But it's great largely because it plays over and against the expectations that Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings created. Lacking The Lord of the Rings, Game of Thrones would be a top-class punchline without the setup – probably still brilliant, but fewer people would get it.

And that brings me back to The Wheel of Time.

Here's why I've found it fascinating: Like Martin, Robert Jordan draws heavily on themes established (or, more accurately, re-popularized) by Tolkien. But, unlike Martin (or later writers like Brandon Sanderson), Robert Jordan isn't flipping those scripts or subverting them. Instead, he's trying to expand them.

I mean that first in a literal sense. Tolkien's series is three books (five, if you're generous and count The Hobbit and The Silmarillion). Jordan's is an utterly overwhelming 14, even before you throw in the extra stuff. At least in terms of word count, it's massive.

But I also mean it in the sense that Jordan doesn't shy away from Tolkien's thematic templates. He's early enough that he actually leans further into them. There are plenty of illustrations, but a few of the most notable are that the hero is from a small town conspicuously similar to The Shire, the evil creatures hunting him are reminiscent of Ring wraiths and orcs, and the good guys are fighting for "The Light" while the bad guys are fighting for "The Dark One".

It's all derivative of typical fantasy tropes. It's generally entertaining enough that I don't mind (too much, at least). And here's why I think it works:

The first Wheel of Time book was published in 1990.

So, after Tolkien, but before Game of Thrones, Assassin's Apprentice, and Harry Potter.

It was a bestseller.

I think, if someone published something similar today, it'd be relegated to the third page of Amazon search results. Because, at this point, too much ground has been tread, and the tropes are tired out. TV shows like Andor (which challenges classic Star Wars expectations) and She Hulk (which remakes the stakes of typical Marvel fare) are indicative of this same phenomenon: We've seen enough heroes' journeys to weary of being put through the same old steps.

Which is why it's been so interesting going back to them.

A Wendell Berry sentiment captures the feeling: "I like the way that the history of the tree shapes the tree. There’s no distinction between the tree and its history."

Berry is talking about the through-lines in his own writing, but his point is applicable to any art (and, probably, to anything at all): Everything is a reaction, an outcome from an input, a response to something else.

Without the "something else," there's nothing, and no chance of understanding it, either.

I've been frustrated with The Wheel of Time for its distorted depictions of female characters, for its questionable plot points, and for Jordan's ham-fisted repetition of the same motifs over thousands (and thousands, and thousands) of words.

But I've loved The Wheel of Time for its place in fantasy's through-line.

It's inextricable from what came after it, just as it owes everything to what came before it. McDonald leads to Tolkien, who leads to Jordan, who gives way to Hobb, to Martin, to Rowling, to Sanderson, to Bardugo, to whoever else, forever.

Art is beautiful.

I'm a nerd.

I'll see you next week.